Peaking. The mysterious zone where athletes find themselves in the perfect state of readiness prior to their competitive event. Do too little and you lose what you trained. Do too much and you’re not recovered for when it matters. With all the data gathering tools at their disposal some of the best strength coaches in the world still get this wrong. There are so many intangibles, and I do not envy the coach who trains an athlete for 4 years leading up to the Olympics who has to try to time everything just right.

With how challenging it is to try to get athletes to their highest state of readiness, imagine how trying to do this for our hero populations? The vast majority don’t have an entire staff dedicated to their strength and conditioning, nutrition, and lifestyle...yet the ones who are on the job always need to be ready to answer the call. To complicate this even more that call can come at any moment. How do you “peak” for any event that can happen at an unknown time and place? The answer is you don’t.

First responders and tactical populations often work nights and erratic hours. Although I would argue nutritional habits are the individual’s responsibility, shift work and the nature of these jobs can make getting in regular meals that our “healthyish” challenging. Then of course, the big one that so many fail to discuss is stress. Stress from everything I have described above as well as the stress from these types of jobs and lifestyles. Seeing societal dysfunction and rot takes a toll on even our toughest people, and it is something that can sneak up on anyone. This obviously applies to soldiers as well.

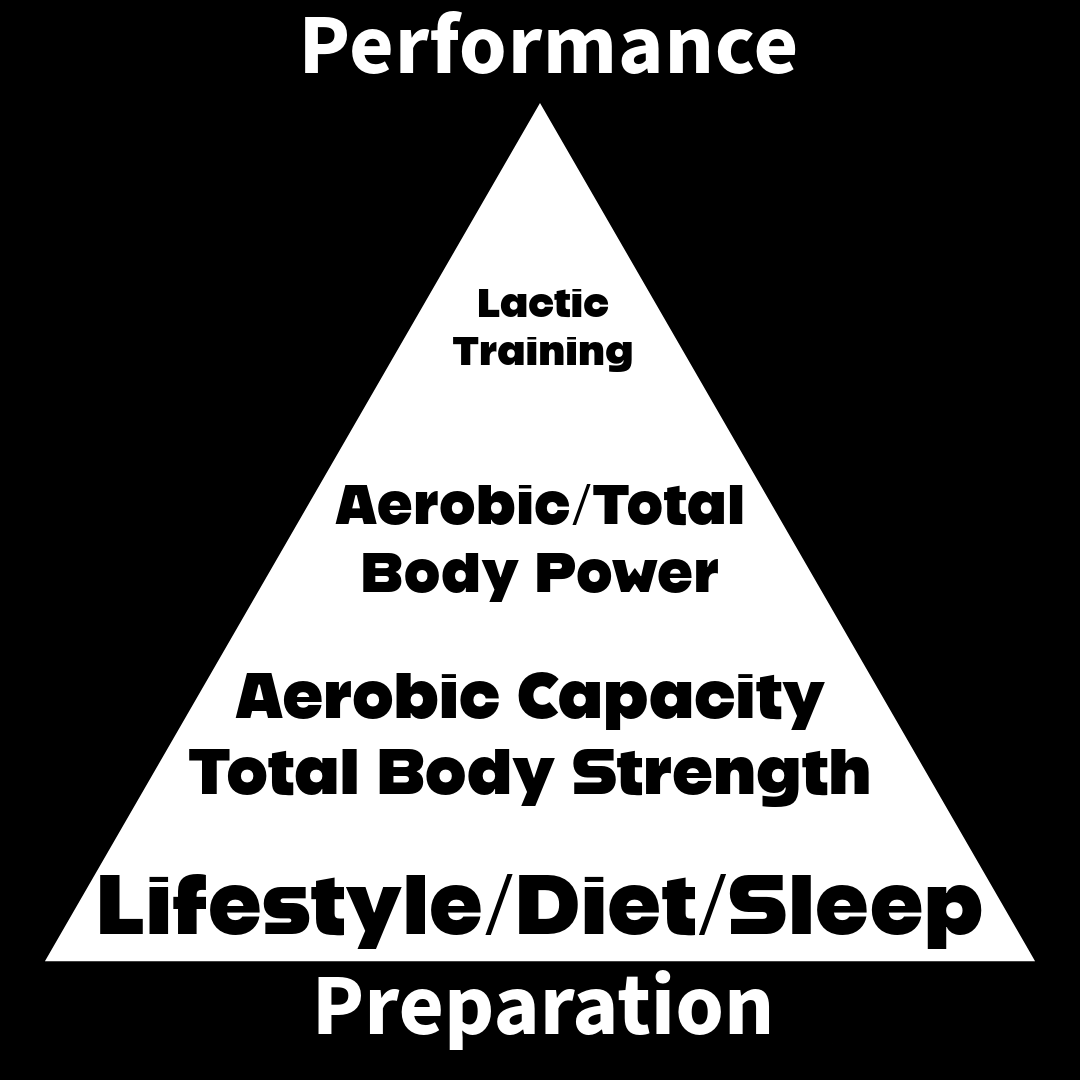

The main theme for our people on the job or already at the unit they want to be at is that most of their training needs to (or should be) in a “moderate” or “medium” zone to allow for a decent level of readiness as opposed to always attempting to be at peak...because it is almost impossible to be able to dial that in. This doesn’t mean training is easy...it just means it should be reasonable the majority of the time, and not always just throwing yourself down a flight of stairs...for time.

In application this means the program is built with a 90/10: 90% of your training should be moderate/easy with high intensity being about 10% of the overall volume. I know some of this might sound redundant as we discussed intensity in the previous article, but all of these concepts are symbiotic. This is how we structure our “Day to Day” monthly programming, and I doubt any of our trainees would say these programs are easy. When we have high intensity days they are crushing. The difference here is we build to it and design the programs so you can recover...which unfortunately is where many other programs fail.

For people heading to SWAT selections or SOF...this can be a bit different. Although peaking is still challenging for these individuals as many of them are still in environments requiring them to train or work tough hours, this can still be an opportunity to add in a bit more volume for a while, and then taper off before the event or school. This still won’t be perfect, as there may be traveling to school, still working a night shift, etc...but it’s better than just continuing to train and not giving yourself an opportunity to recover for a planned event. That is the main difference here...you know when you’re heading to something like this. When you’re on the street or battlefield, you never know what you’re heading into.

As much research that has gone into training athletes for various sports, the reality is hero professions are very hard to fit into a nice category for training. These jobs come with a dynamic lifestyle where a 12 hour shift turns in 16 and you still have to go in the following night. I know how that feels, and if you’re driven, you have to be mature enough to stop yourself and really ask if your planned max effort deadlift session is really what you should do that day, or maybe you just move your recovery day to the day your on...you know...the day you need it…and then when you’re feeling a bit more rested hit the hard workout. Decisions like this over the long term lead to long term progression, which is what you need for a 20 year career.

If you missed the other concepts, read parts 1-3, and let me know if you have any questions in the comments.